For much of the last century, the worlds of film and games seemed to exist on parallel tracks. Film was the home of sweeping narratives, emotional arcs, and visual spectacle. Games, in their earliest form, were seen as playful diversions, systems of rules and challenges rather than spaces for deep storytelling. But over the past few decades, those tracks have bent toward each other, weaving together in ways that have permanently changed how we experience stories. Today, the border between cinema and gaming is porous, with inspiration flowing freely in both directions—something even industries like the 1spin4win slot provider reflect, as game design and cinematic storytelling increasingly overlap.

The Cinematic Evolution of Games

In the late 20th century, as technology matured, developers began to borrow tools and tropes from film. Cutscenes were the earliest and most obvious example: brief, pre-rendered sequences that mirrored the pacing and visual language of cinema. Titles like Final Fantasy VII and Metal Gear Solid used cinematic framing, camera cuts, and voice acting to turn gameplay into something closer to a Hollywood production.

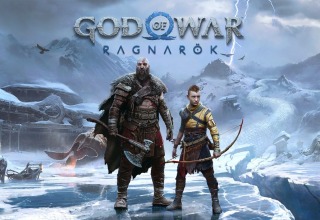

But the influence didn’t stop at surface-level presentation. The structure of films—acts, character arcs, dramatic tension—began to inform how games were written. Games like The Last of Us or Red Dead Redemption 2 are not just adventures; they are character-driven dramas with story beats that could easily be transplanted onto the big screen. The visual grammar of cinema—long shots to build atmosphere, close-ups to capture emotion—has become as essential to modern game design as coding mechanics.

This shift reflects a fundamental desire: players don’t just want to win; they want to feel. Games now use cinematic techniques to ensure that moments of triumph, tragedy, or revelation resonate in ways that mirror the impact of film.

Interactivity Changes the Script

Yet games are not films. Their unique strength is interactivity—the ability to give players agency. This distinction has forced storytellers to rethink narrative flow. While a film locks the audience into a predetermined path, a game asks: what if the audience had the power to choose?

Take Mass Effect, where player decisions ripple through the story and reshape the fate of entire galaxies. Or consider indie titles like Undertale, which subvert expectations by making the player complicit in moral choices, forcing them to reflect on their own role in the narrative. These experiences draw inspiration from film’s storytelling techniques but expand them into new dimensions.

In turn, these innovations are beginning to influence cinema. Interactive films like Black Mirror: Bandersnatch or Netflix’s You vs. Wild borrow the branching narrative concept from games, allowing viewers to shape outcomes. While not yet mainstream, these experiments show that games are not just borrowing from film—they are feeding ideas back into it.

Film’s Borrowed Playbook

Hollywood has long looked to games for source material, though not always successfully. Early adaptations, from Super Mario Bros. (1993) to Street Fighter (1994), treated games as little more than brand recognition opportunities, often stripping away the interactivity and nuance that made the originals compelling.

But the tide has turned. Recent projects like HBO’s The Last of Us have demonstrated that the emotional core of a game can survive—and even thrive—on screen. By respecting the source material and embracing the depth of its characters, the show captured both fans and newcomers. Similarly, animated series like Arcane (inspired by League of Legends) and Cyberpunk: Edgerunners highlight how games can spawn worlds rich enough to support standalone storytelling in television.

The relationship now feels symbiotic: films and series gain from the imaginative scope of game universes, while games benefit from cinematic adaptations that expand their cultural reach.

Technology as the Bridge

Behind this cross-pollination lies technology. Motion capture, once a Hollywood specialty, is now central to game production. Actors like Andy Serkis, Troy Baker, and Ashley Johnson move seamlessly between industries, their performances captured digitally for both big screens and game consoles.

Meanwhile, real-time rendering engines such as Unreal Engine are being used not only in games but also in film and TV production. Disney’s The Mandalorian, for example, used game-engine technology to create its dynamic virtual sets. This shared toolkit has created a feedback loop: innovations in one medium quickly migrate to the other, accelerating creative possibilities.

A Shared Future of Storytelling

As audiences, we live in a golden age of convergence. Games no longer apologize for being “cinematic”; films no longer dismiss games as trivial distractions. Instead, creators are asking how each form can push the other forward.

The rise of transmedia storytelling—franchises that span games, films, comics, and TV—shows how modern audiences don’t just want a story, but a world to inhabit. The Witcher franchise began as novels, exploded through games, and now thrives as a Netflix series. Star Wars, once purely cinematic, has extended into countless games that deepen its lore. These examples illustrate that stories today are not bound by a single medium but thrive in ecosystems of interconnected experiences.

For writers, filmmakers, and developers alike, this convergence is both a challenge and an opportunity. The challenge: to respect the strengths of each medium while experimenting with hybrid forms. The opportunity: to craft stories that resonate not only in passive viewing but in active participation, in play, in choice, and in immersion.

Conclusion: Beyond Screens

The phrase “storytelling beyond screens” is no longer just metaphorical. It reflects a cultural truth: stories today transcend the boundaries of medium, moving fluidly between games, film, and television. Each form borrows from the other, pushing the limits of what’s possible while reminding us that the core of storytelling—connection, emotion, imagination—remains constant.

As technology continues to advance and creative industries intertwine, one thing is certain: the next generation of stories will not simply be watched or played. They will be lived.